Case Title:- Surendra Koli vs. State of UP

Citation:- 2025 INSC 1308

Date:- 11.11.2025

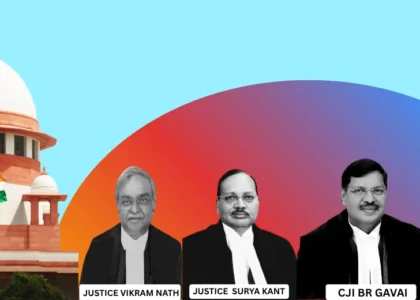

Hon’ble Supreme Court Bench:- CJI B.R. GAVAI, JUSTICE SURYA KANT & JUSTICE VIKRAM NATH

In a landmark ruling reaffirming the primacy of constitutional safeguards and evidentiary discipline in criminal jurisprudence, the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India has set aside the last remaining conviction of Surendra Koli in the infamous Nithari killings case. The judgment, authored by Justice Vikram Nath and delivered by a bench comprising Chief Justice of India BR Gavai, Justice Surya Kant, and Justice Nath, underscores that “arbitrary disparity in outcomes on an identical record is inimical to equality before the law.”

The Hon’ble Supreme Court of India stated that keeping the conviction alive when all other related cases were already found unsustainable would violate Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution.

In this case, the Hon’ble Court has reversed its own earlier judgment which had confirmed Koli’s conviction and death sentence in 2011.

The Nithari killings, uncovered in 2006, shook the conscience of the nation. Human remains found near a house in Noida’s Sector 31 led to the arrest of businessman Moninder Singh Pandher and his domestic help, Surendra Koli. Both were accused of multiple instances of abduction, sexual assault, and murder of women and children. Koli was convicted and sentenced to death in one of the cases in 2011, and that conviction was affirmed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court the same year.

However, in 2023, the Hon’ble Allahabad High Court acquitted both Pandher and Koli in twelve other Nithari cases, observing that the prosecution’s evidence was unreliable and tainted. Later, in July 2025, the Hon’ble Supreme Court dismissed the State’s appeals against those acquittals meaning that in every other related case, the evidence was found to be inadmissible or doubtful.

On this basis, Koli filed a curative petition before the Hon’ble Supreme Court challenging its own 2011 verdict.

A curative petition is the last judicial remedy available in India, created by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Rupa Ashok Hurra v. Ashok Hurra (2002) 4 SCC 388.

In that case, the Hon’ble Court held that even after a review petition is dismissed, the Hon’ble Supreme Court can revisit and correct its own judgment if it results in a manifest miscarriage of justice. Such power is exercised under the Hon’ble Court’s curative jurisdiction, which exists ‘ex debito justitiae’ meaning “as a matter of right of justice.” However, this power is used only in exceptional circumstances where – There is a violation of principles of natural justice, or The judgment was based on evidence or procedure later found to be invalid, unconstitutional, or unjust. In the present case, the Hon’ble Supreme Court found both these conditions satisfied.

The Hon’ble Supreme Court held that allowing Koli’s conviction to stand when all companion cases based on the same evidence had already been declared invalid would amount to arbitrary and unequal treatment under Article 14, and a denial of fair procedure under Article 21. Thus, the Court recognized that its 2011 judgment, which upheld Koli’s conviction and death sentence, could no longer stand after the same evidence had been found inadmissible in other identical cases. The Hon’ble Court noted that maintaining different outcomes on identical evidence would amount to arbitrary disparity, breaching Article 14’s guarantee of equality before law. It added that Article 21’s requirement of a fair, just, and reasonable procedure is at its highest where life and liberty are at stake.

The Hon’ble Court observed that the confession forming the basis of Koli’s conviction was involuntary and legally tainted, and the alleged recoveries failed to meet the conditions under Section 27 of the Evidence Act. Once these were excluded, the Court said, the circumstantial chain collapsed, making the conviction unsustainable.

Criticizing the police investigation as “negligent and procedurally flawed,” the Hon’ble Court observed that lapses in securing the crime scene, preserving forensic evidence, and recording statements had “corroded the fact-finding process.” It reiterated that “suspicion, however grave, cannot replace proof beyond reasonable doubt.”

Citing Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978) and State of Rajasthan v Kashi Ram (2006), the Hon’ble Court reaffirmed that legality cannot be sacrificed for expediency. Upholding the presumption of innocence, it concluded that “when proof fails, the only lawful outcome is to set aside the conviction, even in a case involving horrific crimes.”

By overturning its earlier verdict, the Hon’ble Supreme Court reaffirmed that the rule of law demands fairness, equality, and proof not conjecture even in the most heinous cases.